Early Days

Born

in 1925 into an upper middle-class family in Cincinnati, Ohio, Kenneth

Koch started writing poems and comics as a very young child. He was

encouraged by his dramatic mother, Lilly, by his Uncle Leo (who worked

with Koch’s father, Stuart, in the family’s office furniture

business), and in high school by his English teacher, Katherine Lappa.

With America’s entry into World War Two and the likelihood of

Koch’s being drafted as soon as he graduated from high school

in 1943, he attended the University of Cincinnati for training in

meteorology that spring in hopes of a safe job in the military. However,

Private Koch eventually went to fight in the Pacific with the 96th

Division Army Infantry. Despite losing his glasses, Koch fought from

a foxhole in the battle of Leyte, but a case of hepatitis kept him

from being deployed to Okinawa, where most of his division suffered

very heavy casualties. (Koch would not write about his war experiences

until 50 years later in New Addresses.) He came back to America in

January, 1946, with his copies of View, the surrealist, avant-garde

art and literary magazine, and two months later was enrolled at Harvard.

Studying with Delmore Schwartz, the first “real” poet he

had ever met, led Koch to the work of Yeats and a life-long admiration

for Stevens. His fellow undergraduates at Harvard and Radcliffe included

Robert Creeley, Donald Hall, Robert Bly, and Adrienne Rich, but, most

importantly, John Ashbery, whom Koch met in the fall of 1947 in the

office of the Harvard Advocate, the literary magazine edited

at that time by Koch. Ashbery and Koch became fast friends.

|

Kenneth

Koch around age 4

Kenneth

Koch around age 4

|

Harvard

After

graduating early from Harvard (spring, 1948) because of the additional

credits from the University of Cincinnati and courses he had taken

in the army at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Koch went to

New York City to do graduate work at Columbia University (1949–50).

He kept in touch with Ashbery, still at Harvard, who wrote to Koch

about the work of another fellow undergraduate, Frank O’Hara:

“I think we have a new contender.” O’Hara subsequently

became a lifelong friend, and Ashbery and O’Hara followed Koch

to New York, where he happily introduced them to two young painters,

Jane Freilicher and Larry Rivers, who would also become lasting friends.

France

& Italy

In 1950

Koch went to Paris and Aix-en-Provence as a Fulbright fellow. While

falling in love with the French language, he immersed himself in the

poetry of Apollinaire, Jacob, Reverdy, Eluard, St. John Perse, Breton,

Char, Ponge, and Michaux. Koch returned to New York and his friends,

sharing a house with Rivers and Freilicher in East Hampton in the

summer of 1953 before going off to the University of California at

Berkeley for more graduate work. There he met Mary Janice Elwood,

who eventually followed him to New York and married him in 1954. Koch

was glad to be back in New York and at Columbia University, where

he finished his M.A. thesis, and was ready to begin teaching (at Rutgers).

In addition, during the early 1950s Koch underwent intensive Freudian

psychoanalysis.

During an extended stay in Europe, their daughter, Katherine, was

born in Rome (1955). A return from New York to Florence in 1957 on

Janice’s Fulbright inspired Kenneth to write his first epic narrative

poem, Ko, or a Season Earth, which features a Japanese

pitcher whose fastball has so much velocity it can knock down a grandstand.

Written in ottava rima and iambic pentameter—a verse rhythm Koch

had practiced by using it for his notes in a course at Harvard and

later by learning to speak in it—this comic extravaganza was

inspired by Byron’s witty and digressive Don Juan and

Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso.

Teaching

In the later 1950s Koch resumed teaching at Rutgers and Brooklyn College,

while completing his Ph.D. at Columbia. In 1959 he joined the English

and Comparative Literature department at Columbia, and in his 43 subsequent

years there he proved to be an inspiring teacher known for his spontaneous

wit, good taste, and infectious love of great literature and art,

for which he received the Harbison Award for Distinguished Teaching

(1970). Between Columbia and his influential poetry workshop program

at the New School (1958–66), a surprising number of students

went on to become well-known writers, including David Shapiro, Ron

Padgett, David Lehman, Luc Sante, Bill Berkson, Joseph Ceravolo, Tony

Towle, Peter Schjeldahl, Charles North, and Jordan Davis, as well

as the filmmaker Jim Jarmusch.

|

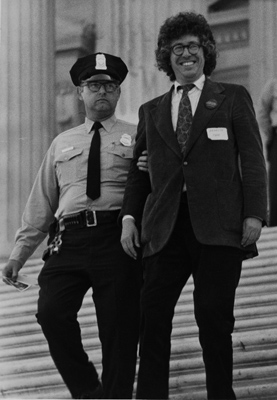

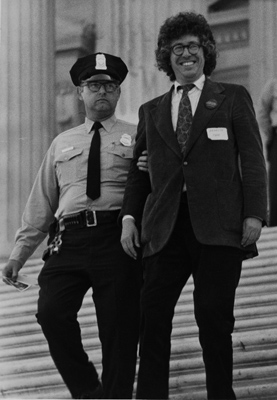

March

on Washington, Nov. 1969

March

on Washington, Nov. 1969

|

In addition

to university teaching, Koch also worked with young children in the

New York City schools, as well as with old people in a nursing home.

His work at P. S. 61 in 1968 led to an important collaboration with

Teachers & Writers Collaborative and resulted in internationally

recognized books about teaching poetry: Wishes, Lies and Dreams:

Teaching Children to Write Poetry; Rose, Where Did You Get that Red?

Teaching Great Poetry to Children; Sleeping on the Wing: An Anthology

of Modern Poetry with Essays on Reading and Writing; I Never Told

Anybody: Teaching Poetry Writing to Old People and Making Your Own

Days: The Pleasures of Reading and Writing Poetry.

Collaborations

Koch was a natural collaborator. As the editor of the groundbreaking

“Collaborations” issue of Locus Solus magazine, he

awakend contemporary readers to the history of literary collaboration.

His own prodigous skills were displayed in an evening of improvisational

collaborations he did with Allen Ginsberg, which were then published

in a book entitled Making It Up.

Koch,

Ashbery, O’Hara, and James Schuyler—the nucleus of the so-called

“New York School”—collaborated not only with each other,

they also collaborated with many other artists and composers.

|

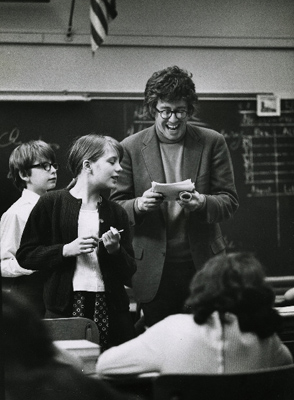

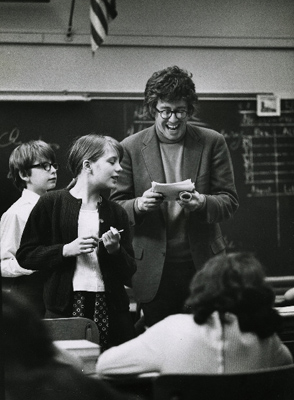

Koch

teaching at PS 61, NYC, 1968

Koch

teaching at PS 61, NYC, 1968

|

Visual

Art

The

poets’ friendships with painters—Willem deKooning, Jackson

Pollock, Franz Kline, Helen Frankenthaler, David Smith, Larry Rivers,

Jane Freilicher, Fairfield Porter, Mark Rothko, Alex Katz, Red Grooms,

Nell Blaine, Alfred Leslie, Joe Brainard, Roy Lichtenstein and Jim

Dine, among others—are legendary: house-sharing during summers

in the Hamptons, evenings at New York’s Cedar Tavern or The Five

Spot, and loft parties. Koch’s collaborations with many of these

visual artists feature his writing on the canvas as the artist painted,

both people changing the images and the words together.

Koch had gallery shows of his collaborations at Tibor de Nagy Gallery

(New York), Guild Hall (East Hampton, N. Y.) and in Ipswich, England.

These shows featured some of the more than 25 “artist’s

books” Koch did with French artist Bertrand Dorny, a series of

maps with Red Grooms, and a “jump-up” book with Larry Rivers.

Plays

Koch’s plays also provided occasions for collaborations with

artists. Alex Katz created the costumes and wooden silhouettes of

men, women, and horses to represent the British and American forces

for George Washington Crossing the Delaware. Among other plays

that have been staged off- and off-off-Broadway, The Red Robins had

celebrated productions with sets by Roy Lichtenstein, Jane Freilicher,

Red Grooms, Alex Katz, Katherine Koch, Rory McEwen, and Vanessa James.

The Construction of Boston was first performed as a collaborative

play starring the three artists involved—Robert Rauschenberg

bringing weather to Boston through a rain machine he constructed;

Niki de Saint Phalle bringing art by shooting a plaster Venus de Milo

statue with a rifle so it “bled” paint of different colors;

and Jean Tingley bringing architecture by constructing a seven-foot

wall on the stage. The production was directed by Merce Cunningham.

This play became another collaboration when Scott Wheeler turned it

into an opera.

|

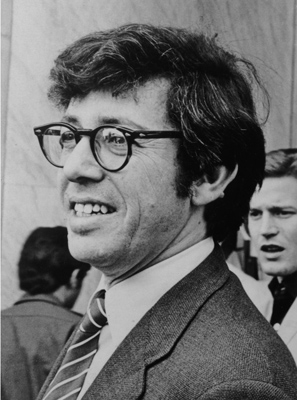

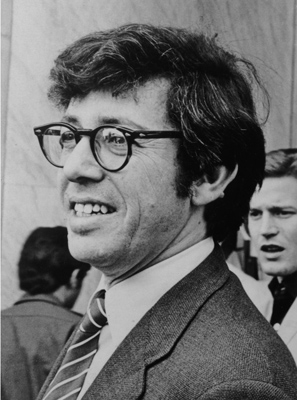

Koch

in the 1970s

Koch

in the 1970s

|

Opera

& Songs

Opera

was one of Koch’s favorite art forms. He said he thought the

perfect job for him would be as a court librettist responsible for

creating at least three opera libretti a year. Some of Koch’s

other plays were set as operas, such as The Gold Standard (also

set by Wheeler) and Départ Malgache set by Roger Trefousse.

In addition, Koch wrote libretti for particular composers to set:

Bertha for Ned Rorem, A Change of Hearts for David Hollister,

and two for music by Koch’s Italian friend Marcello Panni,

The Banquet: Talking about Love and Garibaldi en Sicile.

In addition to opera, individual songs were created from his poems

or poem cycles. Virgil Thomson set Collected Poems, a series

of 39 one-line poems that Thomson later arranged for vocal duet and

chamber orchestra, and four poems under Thomson’s title Mostly

about Love. Ned Rorem set those same four poems and many other

poems by Koch, including To the Unknown. Other song collaborations

include William Bolcom’s setting of Koch’s To My Old

Addresses and two song cycles by Mason Bates, In Bed and

Songs from the Plays.

Movies

Movies with Rudy Burckhardt and Keith Cohen round out Koch’s

collaborations. Many pieces in Koch’s One Thousand Avant-Garde

Plays are produced around the world.

But poetry was always at the center. (For an annotated chronology

of Koch’s books, click here.)

Later

Life

When

Karen Culler, a pianist and education consultant Koch had met in 1977,

moved in with him in 1989, a sort of relaxation came over him. They

married five years later, and until he died (July 6, 2002) Karen was

to remain his wife, friend, astute fan, and energetic traveling companion

on trips to Europe, Africa, Asia, South America, and Antarctica.

For decades Koch had been idolized by young poets, but in his later

years critical esteem for his work finally came to the fore, with

public praise from writers such as Frank Kermode, John Gardner, Thomas

M. Disch, James Salter, David Lehman, Reed Whittemore, Stephen Spender,

Aram Saroyan, Robert Coles, John Hollander, Gary Lenhart, Ken Tucker,

John Ashbery, Jonathan Lethem, and Charles Simic. Volumes of his poetry

appeared in French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Greek, Swedish, and

Danish translation. Koch was elected to the American Academy of Arts

and Letters and won the Bollingen Prize, the Bobbitt Library of Congress

Prize, the Shelley Award for Poetry, and the Phi Beta Kappa Award

for Poetry. He was also a finalist for the National Book Award and

the Pulitzer Prize. The French government made him a Knight in the

Order of Arts and Letters. Koch liked getting prizes and awards but

he never confused them with greatness. A competitive man with high

standards, he spent his life vying happily with his literary heroes

past and present.

Return

to Top

|

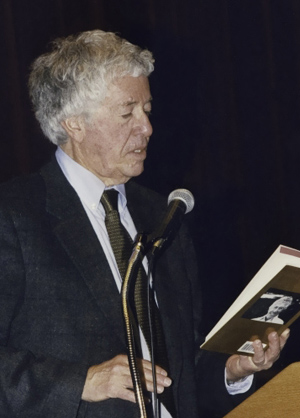

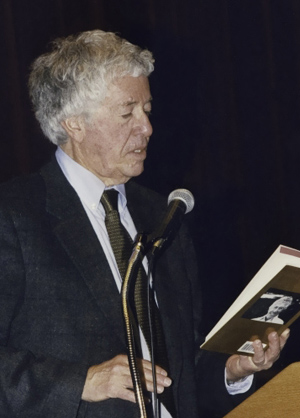

Koch

in the 1990s

Koch

in the 1990s

|